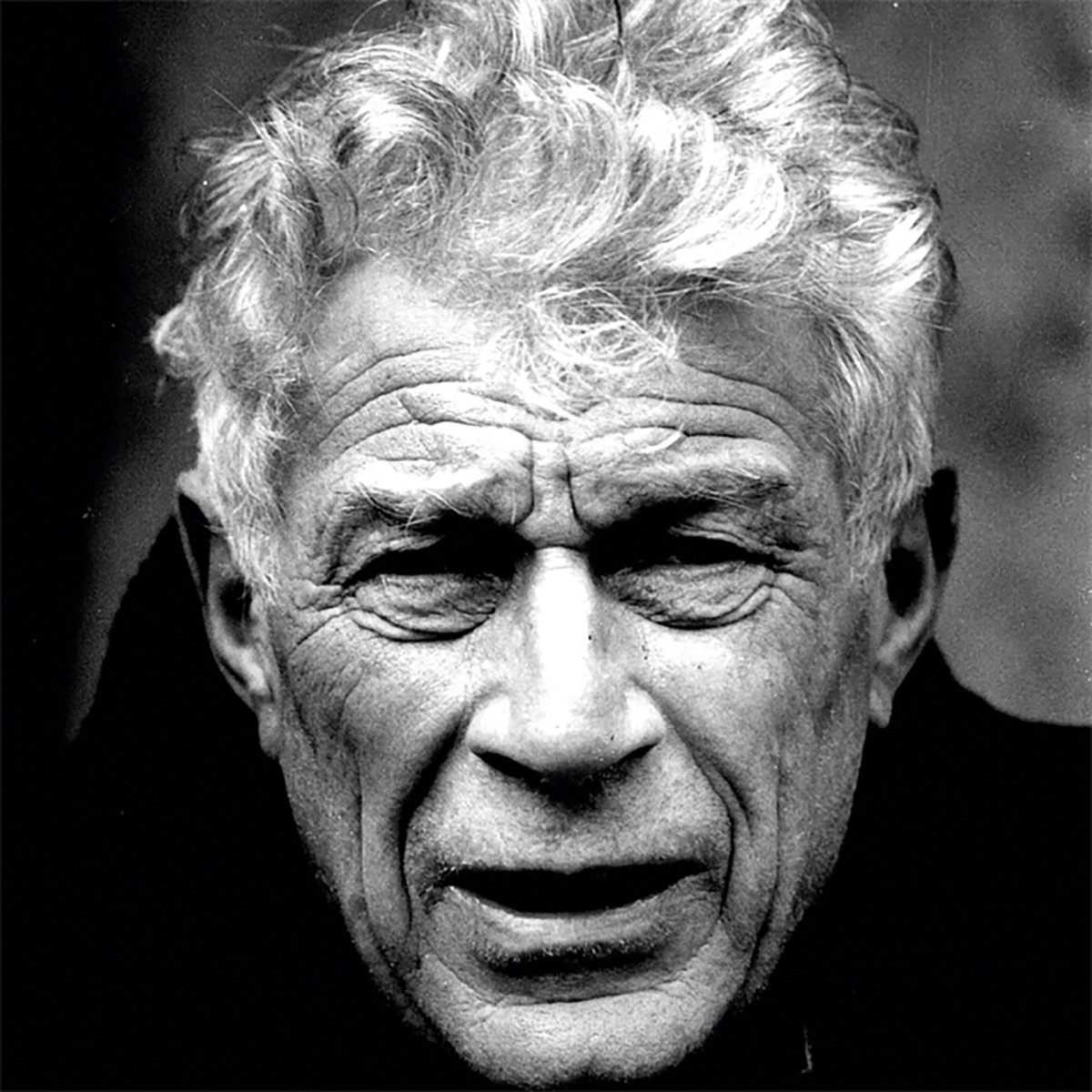

In the art world, John Berger (1926-2017) will likely always be renowned for Ways of Seeing, the paradigm-shifting 1972 TV series and book. It remains essential, and its ideas are the subject of fervent debate when curators working in Berger’s tradition commit them to wall labels alongside historic paintings.

Were Berger’s bullseye description of Thomas Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews (around 1770)—“It is very possible that Mr and Mrs Andrews were engaged in the philosophic enjoyment of unperverted Nature. But this in no way precludes them from being at the same time proud landowners…”—to appear on the painting’s label in the National Gallery, it would be a red rag to critics screaming “woke” at curators and blaming them for declining visitor numbers. But I have explored this subject in previous columns.

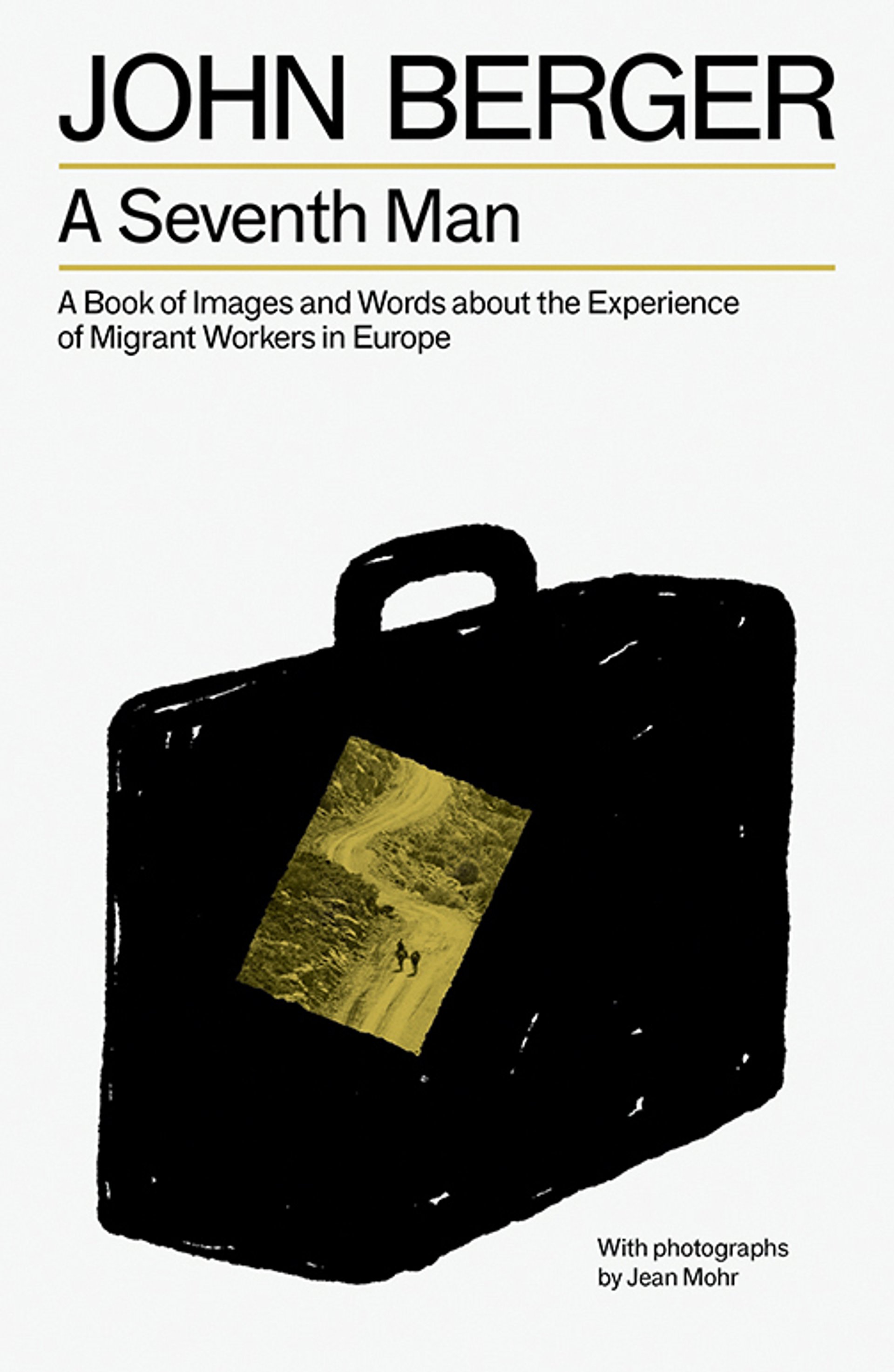

Berger’s enduring importance not just as an art critic but a polymathic writer and thinker is highlighted by two current cultural events. The first is the publication of a new edition of A Seventh Man: A Book of Images and Words about the Experience of Migrant Workers in Europe, which is half a century old this year. Berger’s text is accompanied by photographs mostly taken by his regular collaborator, the Swiss photographer Jean Mohr. Together, they explore how wealthy European economies had become increasingly reliant on the labour of people from poorer, southern European nations.

From text to stage

The second event is the collaboration between Nederlands Dans Theater (NDT), with associate choreographer Crystal Pite, and the theatre collective Complicité, led by artistic director Simon McBurney, called Figures in Extinction, at Sadler’s Wells in London between 5 and 8 November. It features excerpts from two of Berger’s texts: his 2009 book Why Look at Animals? (in which he analysed the steady rupture in the relationship between humans and nature “completed by 20th-century corporate capitalism”) and his 2007 essay Twelve Theses on the Economy of the Dead.

John Berger’s 1975 book A Seventh Man has been published in a new edition

Courtesy Verso Books

When A Seventh Man was reissued in 2010, Berger admitted in the preface that the book had, in certain ways, become outdated: old statistics, for instance, and, fundamentally, a collapse in the Cold War world order. What has not changed is its human conviction. Berger writes that he and Mohr had first considered making a film, but ended up making “a book of moments (recorded in either images or words), and we arranged these moments in chapters which resembled film sequences”. In aspiring to the condition of a documentary, with individuals’ testimony framed with a startling directness not by a movie camera but by Berger’s words and Mohr’s stills, we still viscerally feel their “heroism, self-respect and despair”, as Berger himself puts it.

Berger adds in the preface that, when we look at casual snapshot photographs that have aged over many years, “the normal becomes surprising or moving or sacred, because life too keeps its surprises”. In A Seventh Man, this is true in a different sense, because in Mohr’s photographs, there is perhaps surprise in the changing nature of places and people over time, of cities and spaces, fashions and furniture. Yet the fundamental nature of the images remains entirely routine; we see these kinds of photographs every day in reportage, but often accompanied by the rhetoric of politicians systematically degrading the humanity of the people depicted.

Refusing simplification

I found opening A Seventh Man again troubling, even mournful. Because its prescience is matched by its nuance. Looking back, Berger describes how he and Mohr “weren’t tempted to eliminate the ambiguities, the friction or the recalcitrance of the real… [we had] a fierce discretion which refused simplification”.

As the Figures in Extinction title suggests, the NDT/Complicité performance addresses the extreme effects of humans’ dislocation from nature, the climate catastrophe. But it is not a project born of despair. When talking about Berger in relation to the work on BBC Radio 4’s Front Row earlier this year, McBurney spoke of how Berger was “able to understand that hope itself is a political issue. He used to talk about smuggling hope into our lives and he talked of hope as a form of energy—energy for people who are oppressed, energy which then results in the ingenuity of people.”

This is why Berger is such a significant presence, still. He was a writer beyond the noble occupation of the critic, not just in the forms of literature he engaged in but in his wide-ranging, generation-traversing humanity.